Health Literacy has been understood as literacy applied to health information. But we now know that communication is a dialogue, so even at the federal level, folks understand the need to expand the definition. Healthy People call for comments has been a great opportunity to share ideas. Here’s my contribution to the Solicitation for Written Comments on an Updated Health Literacy Definition for Healthy People 2030 (by the Health and Human Services Department). My definition brings together literacy, plain language, and cultural competence.

Health Literacy has been understood as literacy applied to health information. But we now know that communication is a dialogue, so even at the federal level, folks understand the need to expand the definition. Healthy People call for comments has been a great opportunity to share ideas. Here’s my contribution to the Solicitation for Written Comments on an Updated Health Literacy Definition for Healthy People 2030 (by the Health and Human Services Department). My definition brings together literacy, plain language, and cultural competence.

Health Literacy is the set of world and health knowledge and beliefs, general intelligence and literacy, and communication skills that allows an individual to seek, obtain, understand, assess, and apply health information in daily life and health care contexts. This ability is mediated by:

· the individual’s culture, education, language, and situational and emotional constraints;

· the demands and complexities of the healthcare system;

· the knowledge, beliefs, intelligence, literacy, and communication skills of health care and health information providers who have a responsibility to provide health information in plain language;

· the use of plain language in communication materials. that is, the sharing of information in coherent, cohesive, adequate, and accessible language;

Operationalizing this definition would call for separate assessments for:

– individual health literacy

– provider health communication aptitude

– communications/materials plain language

– system accessibility

Comments

Health communication is an interaction, and, to promote a successful interaction, several factors must come together that include the capacities of the individual and the abilities of health communicators, the clarity of the information and materials used, and the traits of the system in which the health information exchange happens.

Bringing together the dimensions that contribute to or affect successful health communication takes caution. Some proponents of a broad definition of health literacy lift the responsibility of comprehension off the individual to replace it with the obligation for clear communication by the providers or the system.

However, shifting the definition of health literacy away from the individual undermines intervention opportunities. We must consider in parallel individual knowledge and skills—accumulated through experiences and education, and mediated by values, interests, and intelligence—and the knowledge and skills of interlocutors, the clarity of materials, and the intricacies of the system that individuals and providers operate within.

So, rather than one or the other, a wider definition of health literacy must include a multidimensional construct that acknowledges the four dimensions at work. We must also remember that health communication happens not only in disease-driven exchanges but also in health-driven situations that include daily and lifestyle choices.

For these reasons, we should promote a baseline of 21st century knowledge through education: how the human body and the natural world work, what decisions are individual choices (DNR, termination) versus social needs (immunization, right to choose.) Without this, citizens are not equipped to make personal health decisions or weigh in on policy choices. Health education should begin in the early school years and continue throughout life, building on previous knowledge. We should also promote a baseline of 21st century cultural competence through professional training and continuing education. Both of these ideas are discussed by the National Academy of Medicine in A Prescription to End Confusion. Without a doubt, the intricacies, injustices, and inefficiencies of the healthcare system need addressing. While outside the scope of this article, certainly revisiting laws and structural issues is essential for the future. Last, but not least, something we can address from within the community of health communicators is the clarity of materials.

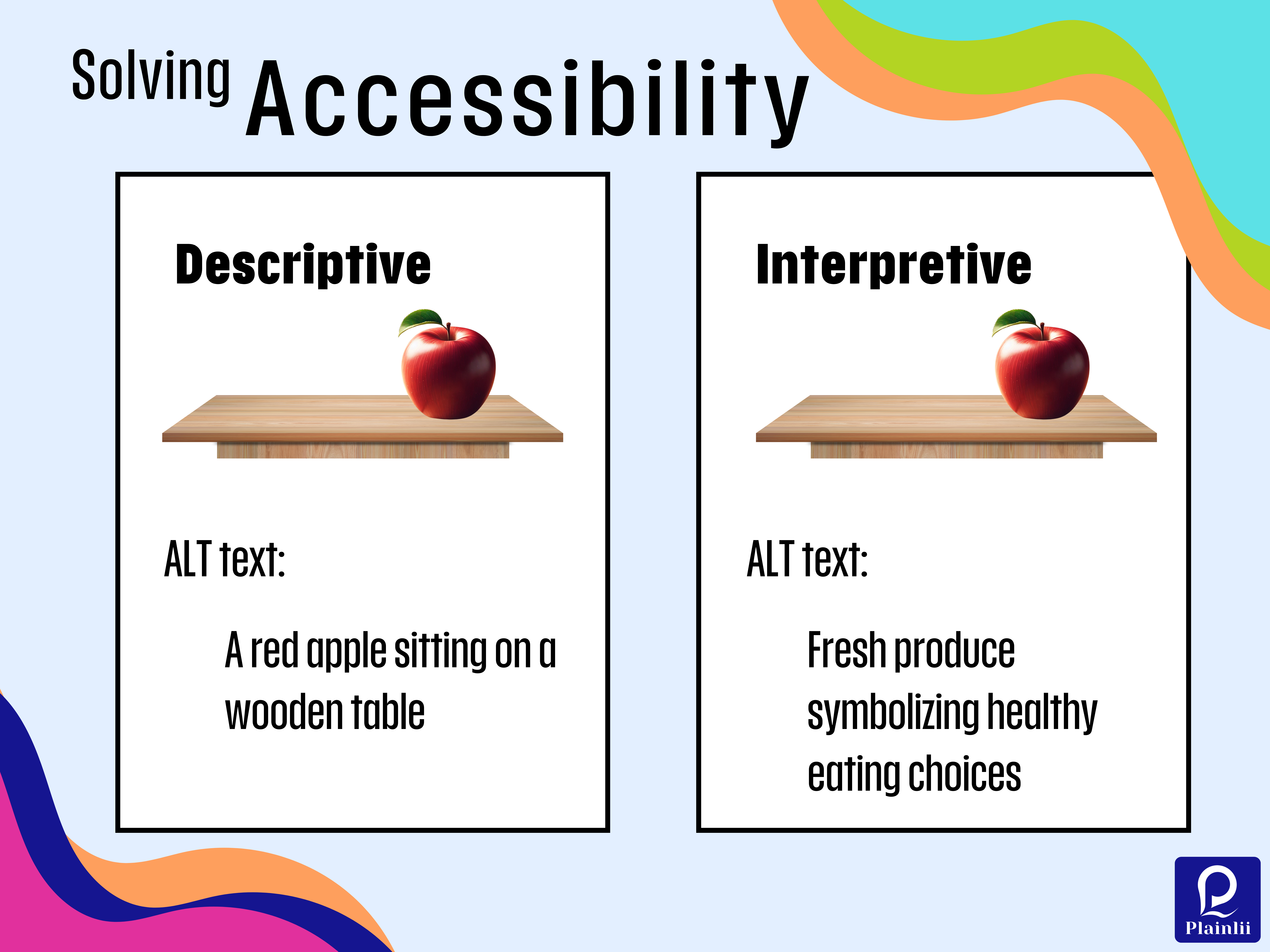

The use of plain language is gaining momentum and we are at a great pivotal moment to dispel some myths about clarity. Plain language started out as clarification and simplification of information for lay audiences. Today, it encompasses a wide range of strategies with the goal of presenting information clearly and adequately to a range of audiences. But, there is no one-size-fits-all plain language set of rules. Clarity among experts in the same field looks different from clarity among non-experts, people with cognitive or physical disabilities, or even experts of different fields.

A crucial point to remember is that quick tips like “use everyday words” or “be specific” belong to different levels of adaptation for clarity. The first one applies to the adequacy of the text for a lay audience (it doesn’t apply to clear technical text). The second one applies to the textuality or coherence of the text for any audience. Every text, no matter its audience, should be as specific as possible: redundancies of content or meandering off topic will confuse any reader.

One last point about individual skills assessments or screenings: they must become more comprehensive. Both oral and written skills matter; but it is important to remember that text is not merely a recording of speech. We should look at developing a more robust tool for health literacy assessment. For academic language skills, a group of researchers led by Paola Uccelli developed CALS (Core Academic Language Skills), an instrument that moved away from a one-dimensional predictor (vocabulary) to a cohort of skills (including complex terms, complex syntax, discourse markers, anaphoric reference, expository text organization, metalinguistic vocabulary, and writer perspective). This is relevant to reconsider health literacy assessments that focus on medical vocabulary as a predictor and expand them to include the knowledge and deployment of a repertoire of language forms and functions that better reflect ability and comprehension.